Japanese New Wave Films (1956 - 1976)

/Funeral Parade of Roses (Credit: Art Theatre Guild)

In the mid-50s, sword-fighting flicks and romantic melodramas were successfully marketed to teenage audiences, but the threat of TV's popularity was just around the corner. The release of Season of the Sun led to taiyozoku (sun tribe) movies, which would center on spoilt youths and their immoral exploits. Smaller, less prestigious studios such as Nikkatsu and Toei would produce provocative genre movies, particularly samurai films and rock musicals, at a rapid rate. Their relentless billing led to a post-war high at the Japanese box office in 1958, which understandably forced larger studios to take notice of audience demand; particularly the traditionally more conservative studio, Shochiku.

Shochiku studios decided to adopt the subject matter seen in Nikkatsu and Toei films, combining it with popular techniques used in French cinema to create the Japanese New Wave. In 1959, assistant director Nagisa Oshima was finally given the opportunity to write and direct his own scripts for Shochiku, a decision that would act as a catalyst for the New Wave's success. With the immediate popularity of Oshima movies, more young assistants would be given opportunities to direct.

Still, box office attendance was plummeting by 1963, and the popularity of television was clearly the industry's major issue. Ticket prices were lowered, but it would take more than that to bring back audiences. The best option for studios would be create titles that would offer an alternative to televisual productions. This meant a rise in violent swordplay, soft-core pornography and the introduction of yakuza pictures.

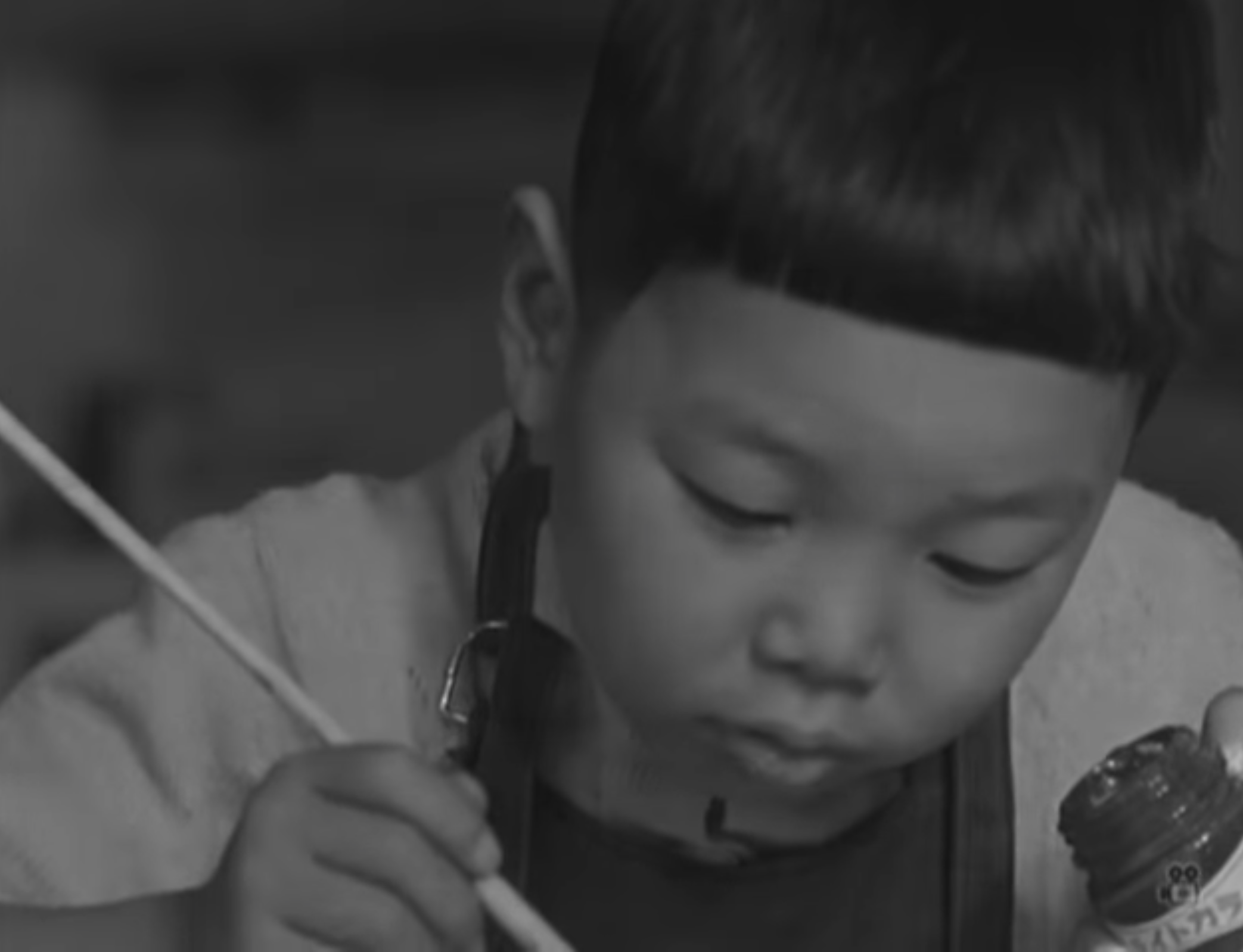

Children Who Draw (1956) Te o kaku kodomotachi by director Susumu Hani

Children Who Draw (1956) Credit: Teizo Otuchi

Using the contrast between color and monochrome photography to explore the inspiring outlook of children, Children Who Draw explores the imaginative creations of young art students. Susumu Hani's explorational, lingering camera movements have drawn comparisons to the work of The Left Bank's Alain Resnais.

Punishment Room (1956) Shokei no heya by director Kon Ichikawa

Punishment Room (1956) Credit: Daiei Studios

A disrespectful student humiliates his father and continues to goad rival gangs. He rapes a girl in his class, who becomes infatuated with him. Eventually, his immoral ways catchup with him while trying to prove his courage. The film was based on the novel of the same name by Shintarô Ishihara.

Crazed Fruit (1956) Kurutta kajitsu by director Kō Nakahira

Crazed Fruit (1956) Credit: Nikkatsu

While spending a summer by the beach, two brothers fall for the same girl. However, her infatuating charm disguises that there is more to the beautiful woman than meets the eye. Crazed Fruit is also known as Juvenile Jungle, and is an example of Sun Tribe cinema.

Suzaki Paradise Red Light (1956) Suzaki Paradaisu: Akashingô by director Kawashima Yuzo

Suzaki Paradise Red Light (1956) Credit: Nikkatsu

Tsutae and Otoku contemplate their passionless future and travel to Suzaki. They see a sign for Suzaki Paradise, a red-light district where Tsutae used to work as a prostitute. She finds a job as a waitress, while Otoku makes a living delivering noodles. However, Tsutae is soon attracted a wealthy man who owns a radio store.

A Sun-Tribe Myth from the Bakumatsu Era (1957) Bakumatsu taiyôden by director Yûzô Kawashima

A Sun-Tribe Myth from the Bakumatsu Era (1957) Credit: Nikkatsu

In the Shogunate's final days, a grifter must outwit the inhabitants of a brothel in order to survive. The film is also known as Sun in the Last Days of the Shogunate.

Kisses (1957) Kuchizuk by director Yasuzo Masumura

Kisses (1957) Credit: Daiei Studios

Kuchizuk tells the story of a young couple who face the imprisonment of their fathers.

Warm Current (1957) Danryu by director Yasuzô Masumura

Based on Kunio Kishida's novel, Danryu shows a doctor running a small hospital. To his dismay, he must choose between two very different women.

Giants and Toys (1958) Kyojin to gangu by director Yasuzô Masumura

Giants and Toys (1958) Credit: Daiei Films

During a fierce competition between caramel companies, an worker recruits a teenage girl to become a mascot. Giants and Toys was written by Takeshi Kaikō, who also wrote the novel, which takes a satirical look at the incredible devotion Japanese workers show towards their companies.

The Assignation (1959) Mikka by director Kō Nakahira

The Assignation (1959) Credit: Nikkatsu

Kikuko is bored of her marriage to an older man, who works as a university professor. In a cruel twist of fate, she falls for one of his students.

A Town of Love and Hope (1959) Ai to kibô no machi by director Nagisa Ôshima

A Town of Love and Hope (1959) Credit: Shochiku

A wealthy woman takes an interest in a man who scams others out of money. Believing in him, she wants to help find him a better life and an honest job.

Naked Youth (1960) Seishun zankoku monogatar by director Nagisa Ôshima

Naked Youth (1960) Credit: Shochiku

A young man seduces a woman with a knack for attracting middle-class men. Posing as hitchhikers, they commit a series of robberies. The film is also known as A Cruel Story of Youth.

The Sun's Burial (1960) Taiyô no hakab by director Nagisa Ôshima

The Sun's Burial (1960) Credit: Shochiku

Taking place in an Osaka slum, those with few future prospects turn to a life of crime.

Night and Fog in Japan (1960) Nihon no yoru to kiri by director Nagisa Ôshima

Night and Fog in Japan (1960) Credit: Shochiku

On a former activist's wedding day, uninvited guests accuse the couple of forgetting their political responsibilities. A series of flashbacks then explores past events, centering on student activism in the 1950s.

In 1948, anarchist students formed the Zengakuren, looking to immobilize students against a treaty with the United States known as AMPO (Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan). Ôshima's film explores this time period with flashbacks, including the demonstrations against the treaty that ultimately failed. Following in their footsteps, the next generation of students also had street protests (which also failed to stop a renewal of the treaty). In 1960, the Zengakuren were trying to separate themselves from the Japanese Communist party, which is the conflict Night and Fog in Japan explores. Above all else, Ôshima's film begs for political reflection, regardless of your allegiance.

Night and Fog in Japan was pulled from release after just three days, due to the assassination of Japanese Socialist Party politician Inejiro Asanuma by a far-right student. Director Nagisa Ôshima saw this as unnecessary censorship, and accused the studio of lacking faith in their audience's ability to view political films.

The Naked Island (1960) Hadaka no shim by director Kaneto Shindô

The naked island (Credit: Kindai Eiga Kyokai)

Hadaka no shim is the story of a family's struggles while living on a small, otherwise uninhabited island. The film has no dialogue and acts as a documentary-like look at the struggles of working class families.

The Warped Ones (1960) Kyônetsu no kisets by director Koreyoshi Kurahara

When a juvenile delinquent is finally free, he seeks to cause chaos, focusing on the girlfriend of a journalist responsible for his imprisonment.

Nikkatsu's The Warped Ones is another example of the studio's Sun Tribe resurgence, reusing elements from 1959's The Time of Youth. Toshirō Mayuzumi's jazz score makes a notable contribution to the film's action.

Bad Boys (1961) Furyo shone by director Susumu Hani

Once again using documentary-like, improvisational styles, Susumu Hani's Bad Boys depicts life in a boys' reform school. The film is known for using non-professional actors, hand-held photography and location shooting.

Pigs and Battleships (1961) Buta to gunkan by director Shōhei Imamura

A young man joins a criminal organization during a time of internal unrest and hostility.

After losing WWII, Japan was occupied by the United States. With General Douglas McArthur in charge, the country was mostly demilitarized and a new constitution was drafted. The occupation ended in 1952, but American military bases continued to exist in the country, leading to protests from Japanese citizens (the same AMPO protests discussed in Night and Fog in Japan).

Because the yakuza were in clear opposition with communist ideals, their prominence had grown rapidly while Japan was occupied by American forces. For example, crime leader Yoshio Kodama was released from prison by the U.S. under the agreement that he would be a threat to potential communist movements. The country's disarmament made life easier for the yakuza, and food rations also led to a rise in black market activity. In fact, Imamura himself had been involved in the black market soon after WWII, before being an assistant to Yasujiro Ozu.

Shōhei Imamura researched organized crime extensively for the film, meeting regularly with the real-life gangsters he found most interesting. The hugely controversial film caused Imamura to be banned by Nikkatsu for two years. Within that time, he would develop numerous screenplays.

In the U.S., a dubbed, recut version of Pigs and Battleships was released as The Dirty Girls and later as The Flesh Is Hot – a key example of how Imamura’s films were presented as soft-core pornography for the American audience.

The Catch (1961) Shiiku by director Nagisa Ôshima

Towards the end of WWII, an American pilot is imprisoned by Japanese villagers. They await instructions on what to do with their prisoner.

A Wife Confesses (1961) Tsuma wa kokuhaku suru by director Yasuzô Masumura

A woman is on trail for the murder of her husband, who died while climbing a mountain. Although she may be innocent, the revelation of an affair, supposedly with her husband's approval, complicates matters further.

Shiro Amakusa, the Christian Rebel (1962) Amakusa Shirô Tokisada by director Nagisa Ôshima

In 1637, Tokugawa-era Japan, a group of Christian peasant revolt against the shogunate. They are helped by Shiro Amakusa, a charismatic and rebellious leader.

Pitfall (1962) Otoshiana by director Hiroshi Teshigahara

Pitfall (Credit: United Artists)

Seeking out work, a man and his son walk through a deserted mining town. However, they will soon discover that the town isn't as empty as it looks, when the town's lost souls begin to appear.

Pitfall is a socially aware drama is also sympathetic towards the 1960 protests against the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security Between the United States and Japan. The film includes stock footage of poverty stricken areas and genuine mining disasters.

This surrealist film marked Hiroshi Teshigahara's directorial debut. The director is closely associated with novelist Kobo Abe, who wrote the screenplay. The pair, along with composer Toru Takemitsu, would go on to collaborate on three more titles, The Face of Another, Woman in the Dunes and The Ruined Map.

The film was released by the Japan Art Theatre Guild (ATG), which began distribution in 1962.

Akitsu Springs (1962) by director Yoshishige Yoshida

Taking place near a thermal spring, a post-war romance blossoms between an innkeeper and a man suffering from tuberculosis.

She and He (1963) Kanojo to kare by director Susumu Hani

A middle-class woman comes to realize the state of poverty in her neighborhood when she meets a beggar and his blind orphan on the street.

In the same year, lead actress Sachiko Hidari won the Silver Bear at the 14th Berlin International Film Festival for her performance in Shohei Imamura's The Insect Woman.

The Insect Woman (1963) Nippon konchûki by director Shōhei Imamura

Life story of a woman born in poverty trying to succeed. Through her many schemes, she faces her ups and downs in a cyclical nature, fueled mostly by self-interest.

By 1964, many New Wave directors had grown tired of their studios and consequently decided to leave. This led to the creation of the Art Theater Guild (ATG), which would finance and distribute key films of the Japanese New Wave. With new-found freedom, the movement's political messages grew stronger, often criticizing the country's authoritarianism and the immorality of Japan's criminal underworld.

Onibaba (1964) by director Kaneto Shindo

onibaba (Credit: Tokyo Eiga)

Shortly after the Battle of Minatogawa (during the 14th Century civil war), a woman and her daughter-in-law make ends meet by killing soldiers and stealing their weaponry. When the arrival of a male neighbor tests the women's unity, a terrifying demon mask appears sends the trio into despair.

Onibaba is heavily inspired by the Shin Buddhist parable, yome-odoshi-no men (bride-scaring mask), which centers on a mother who uses a mask to terrify her daughter and prevent her from going to a temple. However, the mask then turns against the mother.

In interviews about the film, director Kaneto Shindo has stated that the mask is a symbolic discussion of the disfigurement of Japanese citizens as a result of atomic bombings in WWII.

Intentions of Murder (1964) Akai satsui by director Shōhei Imamura

Also known as Unholy Desire, Imamura's Akai satsui centers on a housewife living with a loveless husband. Her life takes a sudden turn when she is raped by a burglar, who then falls madly in love with her.

Assassination (1964) Ansats by director Masahiro Shinoda

As American warships approach the Japanese coast in 1863, a ronin becomes a central figure in the conflict between the empire and the Shogunate. Ansats is based on the Ryôtarô Shiba novel of the same name.

Just like Shōhei Imamura, Masahiro Shinoda had also been an assistant to Yasujiro Ozu, before making his directorial debut with One-Way Ticket for Love in 1960.

Pale Flower (1964) Kawaita hana by director Masahiro Shinoda

When a Yakuza hitman gets released from prison, he must learn to cope with the new power hierarchy. While learning about the change in situation, he also looks to take care of a beautiful woman with a gambling addiction.

Pale Flower is a Japanese noir loosely inspired by Charles Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du mal. It is considered to be a key addition to the Japanese New Wave, and continues to be praised for its pitch-black, alluring tone.

Gate of Flesh (1964) Nikutai no mon by director Seijun Suzuki

Based on Taijiro Tamura's novel, the film shows an injured criminal on the run. He finds shelter in a Tokyo brothel, inhabited by a group of ruthless women.

Due to Nikkatsu's strict production deadlines, Gate of Flesh developed a distinctive visual style; While racing against time to create a firebombed Tokyo ghetto in the studio, production designer Takeo Kimura was forced to use whatever materials were available around the studio backlot.

Tattooed Life (1964) Irezumi ichidai by director Seijun Suzuki

After 'Silver Fox' Tetsu is set up by his own band of criminals, the talented hitman flees to Manchuria with his brother. But with the Japanese police force and the Yakuza hot on their tails, can the duo escape to China with their lives?

Woman in the Dunes (1964) Suna no onna by director Hiroshi Teshigahara

Woman in the Dunes (Credit: Toho)

While taking a vacation, an entomologist is trapped in the desert by local villagers. While imprisoned in a house largely consumed by sand, he must coexist with an enslaved woman being used to shovel sand.

Woman in the Dunes is another collaboration between Hiroshi Teshigahara, novelist Kobo Abe and composer Toru Takemitsu.

The Song of Bwana Toshi (1965) Bwana Toshi no uta by director Susumu Hani

While traveling to Africa for an exchange program, a Japanese man discovers he has been living a lie.

A Fugitive From the Past (1965) Kiga kaikyô by director Tomu Uchida

A criminal turns on his band of thieves in the midst of a heist. Having killed his two partners, he finds shelter with the help of a prostitute. Ten years later, the reason behind his betrayal comes to light. A Fugitive From the Past is based on Kiga Kaikyo, a novel by Tsutomu Minakami.

With Beauty and Sorrow (1965) Utsukushisa to kanashimi to by director Masahiro Shinoda

With Beauty and Sorrow (Credit: Shochiku)

Ôki is a famous novelist, best known for writing about a true love story of his own that tragically ended. His past lover is now a painter who still struggles with their dark history. 24 years later, Oki plans to visit his old flame, but his arrival will surely open up old wounds. The film is based on Yasunari Kawabata's Beauty and Sadness.

A Story Written With Water (1965) Mizu de kakareta monogatari by director Yoshishige Yoshida

A soon-to-be married man finds himself having to choose between his fiancée and his mother. As his inner conflict unfolds, the film explores his past experiences and innate desires. Director Yoshishige Yoshida is known to particularly admire Michelangelo Antonioni and Alain Resnais, which is evident throughout A Story Written With Water and the rest of his work.

Thirst for Love (1966) Ai no kawaki by director Koreyoshi Kurahara

After her husband's death, a woman becomes sexually involved with her father-in-law. Now living with her in-laws, she also finds herself sexually attracted to a young gardener.

Bride of the Andes (1966) Andesu no hanayom by director Susumu Hani

A Japanese mail-order bride travels to Peru to meet her new husband, a Japanese archeologist. While her husband works on Inca ruins, she must adapt to her new life.

The Pornographers (1966) Erogotoshi-tachi yori: Jinruigaku nyûmo by director Shōhei Imamura

A pornographer tries to stay out of trouble with a local gang, as well as the police, while juggling his work with complicated family life. To make matters worse, the man, who has a mistress and a wife, also finds himself attracted to his step-daughter. The Pornographers is based on Akiyuki Nosaka's novel, Erogotoshitachi.

In Ian Buruma’s Behind the Mask, Imamura’s works (including The Pornographers) are used as examples of female worship in Japanese cinema. In Buruma’s view, the women in Imamura’s films “veritably reek of mud“ and are “just as motherly” as the heroines regularly seen in Kenji Mizoguchi features.

Violence at Noon (1966) Hakuchû no tôrim by director Nagisa Ôshima

Two women must learn to accept the dark reality of a man they share a bond with. Oshima's widescreen compositions throughout the film show the director's innovative techniques while discussing social decay.

Fighting Elegy (1966) Kenka erejî by director Seijun Suzuki

Set in the 1930s, a young man wishes to repent his sins and repress his desires for a Catholic girl. Confused and alone, he turns violent as a result of his inner conflict. Fighting Elegy is an adaptation of the first half of Takashi Suzuki's novel of the same name. The script was adapted by Kaneto Shindo, although Suzuki then took many notable liberties with the original script. The film was intended to have a sequel, which would adapt the second half of Takashi Suzuki's novel, but Seijun Suzuki would ultimately be fired by Nikkatsu before the project could begin production.

Tokyo Drifter (1966) Tôkyô nagaremon by director Seijun Suzuki

tokyo drifter (Credit: Nikkatsu)

A yakuza member's ambition to leave his life of crime is scuppered by rival gangs who want him dead.

At this point in Suzuki's career, Nikkatsu had already issued a number of warnings to the director regarding his radical visual style. Despite this, Tokyo Drifter pushes these boundaries further, resulting in an avant-garde, surrealist gangster flick that draws influences from pop art and musical cinema. Nikkatsu would consequently only allow Suzuki to film his next feature on black and white film.

The Face of Another (1966) Tanin no kao by director Hiroshi Teshigahara

A disfigured man seeks out surgery and obtains a mask from his doctor. Initially seen as a success, the experiment takes a dark turn when the mask starts to change his personality. The Face of Another is another collaboration between Hiroshi Teshigahara, Kobo Abe, Hiroshi Segawa and Toru Takemitsu, and is the final installment of their unofficial trilogy. Kobo Abe also wrote the novel of which the film is based, Tanin no kao.

Teshigahara also collaborated with sculptor Tomio Miki and architect Arata Isozaki to create the film's unusual aesthetic.

A Man Vanishes (1967) Ningen jôhatsu by director Shōhei Imamura

When a salesman mysteriously disappears, director Shohei Imamura follow the man's fiancée throughout the investigation. Imamura plays on the audience's perception of reality and fiction as he blurs the lines between documentary filmmaking and conventional storytelling.

Band of Ninja (1967) Ninja bugei-chô by director Nagisa Ôshima

After a feudal lord is murdered, his son encounters a ninja helping peasants rebel against a cruel regime. Unusually for the Japanese New Wave, the film is an animation that uses black and white manga drawings.

Sing a Song of Sex (1967) Nihon shunka-kô by director Nagisa Ôshima

Sing a Song of Sex (Credit: Criterion)

When they should be studying for entrance exams, a group of teenagers fantasize about their classmate. They encounter a drunk teacher, pushing them further down a troubled path. Sing a Song of Sex is particluarly celebrated for its cinematography by Akira Takada.

Branded to Kill (1967) Koroshi no rakui by director Seijun Suzuki

A hitman finds himself fighting against his own organization after a poorly executed job. As his sense of identity spirals out of control he is tracked by the deadliest assassin around, having earned the title of 'Number One Killer'.

Branded to Kill is another experimental take on the gangster genre from Seijun Suzuki. Nikkatsu were unhappy with the production even before shooting began, particularly due to the film's satirical tone and absurdist ideas. The director was let go once the film was a commercial failure, leading to a lawsuit issued by the director. With the support from fellow filmmakers and student groups, the court case became a major controversy within the Japanese film industry. The successful lawsuit, along with Suzuki's unique directorial style, meant that he would be blacklisted for the next decade. He would, however, gain even more popularity as a counterculture figure within the industry.

Inferno of First Love (1968) Hatsukoi: Jigoku-hen by director Susumu Hani

A young goldsmith haunted by his past falls in love with a nude model. Among critics, the film is thought to be one of Sasumu Hani's most important works.

The Profound Desire of the Gods (1968) Kamigami no fukaki yokubô by director Shōhei Imamura

A Tokyo engineer is sent to drill a well on a tropical island riddled with drought. He meets a family of inbred who are despised by the local community.

Summer in Narita (1968) Nihon Kaiho sensen: Sanrizuka no nats by director Shinsuke Ogawa

In this documentary focused on Narita's Youth Brigade, the group take on riot police while protesting against the construction of Narita Airport. The film is the first of a series of documentaries focused on the area known as the 'Sanrizuka'.

Death by Hanging (1968) Kôshikei by director Nagisa Ôshima

Death by Hanging (Credit: Art Theatre Guild)

A Korean man is sentenced to death by hanging. However, his executioners struggle to decide how to proceed after he survives the execution. The film is a black farce, inspired by Ri Chin'u, a Korean man that murdered two Japanese girls in 1958. Despite his actions, director Nagisa Oshima admired Chin'u's abilities as a writer. Throughout the film, he explores the morality of the death penalty, the treatment of Koreans in Japan and a killer's notion of accountability.

Three Resurrected Drunkards (1968) Kaette kita yoppara by director Nagisa Ôshima

Based on The Folk Crusaders' hit song 'Kaette kita yopparai', Three Resurrected Drunkards centers on three men who are mistaken for illegal immigrants from Korea. The mistake takes the carefree trio on a trail of misadventure. Albeit in a different manner to Death by Hanging, the film is another comment from Oshima regarding the treatment of Koreans in Japan.

The Man Without a Map (1968) Moetsukita chiz by director Hiroshi Teshigahara

A detective tries to find a missing man, but contradictory evidence frustrates him as the case begins to seem unsolvable. The film marks the final collaboration between Hiroshi Teshigahara and Kobo Abe.

Aido: Slave of Love (1969) Aido by director Susumu Hani

A beautiful woman is cursed with intense sexual desires, leading her to begin an affair with a student. As she seeks out more sexual partners, the lines between fantasy and reality begin to blur. The film is considered to be a classic example of exploitation cinema in the 1960s.

Ryakushô Renzoku Shasatsuma (1969) Ryakushô renzoku shasatsum by director Masao Adachi

Centering on a serial killer called Norio Nagayama, Adachi's documentary explores the famed murderer's life and living quarters.

When he was 19 years old, Norio Nagayama murdered four people in 1969. He was eventually sentenced to death for his crimes, but used his time in prison to write a number of successful novels. This made him a public figure within Japan, and his name became synonymous with the death penalty debate. Understandably, this has made Ryakusho Renzuko Shasatsuma a more valuable work than Adachi could have known at the time of production.

Eros + Massacre (1969) Erosu purasu gyakusatsu by director Yoshishige Yoshida

Taking place in two time periods, Yoshishige Yoshida's film links a man's belief in free love and anarchism with the students of 1960s Japan. The film explores the exploits of Sakae Osuga, an anarchist having a relationship with three women in the 1920s, while a group of students research his theories in the 1960s.

Eros + Massacre is widely considered to be one of the Japanese New Wave's greatest achievements. Blending a unique avant garde visual style with progressive philosophies on how to challenge societal constraints.

Funeral Parade of Roses (1969) Bara no sôretsu by director Toshio Matsumoto

Funeral Parade of Roses (Credit: Art Theatre Guild)

Applying Sophocles' Oedipus Rex to Tokyo's 1960s underground gay scene, Funeral Parade of Roses tells the turbulent lives of transvestites living in Japan. The film contains some of the same footage as Matsumoto's short film, For My Crushed Right Eye. The film's experimental techniques would go on to inspire Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange.

Boy (1969) Shônen by director Nagisa Ôshima

Based on real newspaper reports, Boy follows an adolescent who must reluctantly help his father's criminal scheming.

Diary of a Shinjuku Thief (1969) Shinjuku dorobô nikki by director Nagisa Ôshima

A thief is caught red-handed by a saleswoman. Due to a surprising turn of events, they embark on an adventure together throughout Tokyo's Shinjuku district. The film explores themes of youths in revolt and sexual liberation.

Double Suicide (1969) Shinjû: Ten no Amijim by director Masahiro Shinoda

Based on Monzaemon Chikamatsu's The Love Suicides at Amijima, the film explores a doomed relationship between a merchant and a courtesan.

Notably, The Love Suicides of Amijima is typically performed using Japanese puppetry. This explains some of the film's experimental techniques and Shinoda's non-realist approach, such as the use of kuroko; stagehands who dress in black and interact with the actors.

Go, Go Second Time Virgin (1969) Yuke yuke nidome no shojo by director Kōji Wakamatsu

A nineteen year-old girl is raped by a group of men on a city rooftop. She opens up about her emotional trauma to a teenage boy, who also reveals that he is a victim of sexual abuse. However, their day-long encounter only leads to further turmoil.

History of Postwar Japan as Told by a Bar Hostess (1970) Nippon Sengoshi - Madamu onboro no Seikatsu by director Shōhei Imamura

In an attempt to show the impacts of war from a new perspective, Imamura's documentary centers on a bar hostess's life in post-war Japan. Although he had made A Man Vanishes in 1967, this film marks the beginning of Shohei Imamura's ten-year devotion to documentary filmmaking, before returning to fictional work in 1979.

The Man Who Left His Will on Film (1970) Tôkyô sensô sengo hiwa by director Nagisa Ôshima

When a student's camera gets stolen, a mystery unfolds after the the thief commits suicide. However, a closer look poses questions about the metaphysical ordeal's authenticity.

The Scandalous Adventures of Buraikan (1970) Buraikan by director Masahiro Shinoda

Due to an increase in immoral laws are passed, the residents of Edo's red light district are forced to rebel.

The Ceremony (1971) Gishiki by director Nagisa Ôshima

When a man receives some distressing news via telegram, he recounts moments from the past, including his dark family secrets. Throughout the film, Oshima satirically highlights certain Japanese values.

Emperor Tomato Ketchup (1971) Tomato Kecchappu Kôtei by director Shuji Terayama

Terayama's experimental short film shows a country where children have seized control.

Throw Away Your Books, Rally in the Streets (1971) Sho o suteyo machi e deyou by director Shuji Terayama

In an attempt to distance himself from his dysfunctional family, a moody teenager hits the streets. He becomes determined to make something of himself, which is in direct opposite to his family, who are content with their current social status. The film discusses an apparent rise of materialism in Japan at the time.

Mandara (1971) by director Akio Jissôji

Students decide to join a sex cult with a mysterious leader devoted to creating a 'prehistoric utopia'. Showing his diversity as a director, Akio Jissoji would later direct the famed superhero kaiju movie, Ultraman.

Summer Soldiers (1972) Samâ sorujâ by director Hiroshi Teshigahara

A Vietnam veteran deserts the US military while visiting Japan.

Dear Summer Sister (1972) Natsu no imôto by director Nagisa Ôshima

In search of her long-lost brother, a girl from Tokyo explores Okinawa island. However, she then discovers that they may have already met. The film shows the enduring effects WWII had on Okinawa Island.

Karayuki-san, the Making of a Prostitute (1973) Karayuki-san by director Shōhei Imamura

Imamura's documentary tells the story of the 'karayuki-san'; women who were forced into prostitution during WWII and sent to Japanese-occupied territories. The film centers on a karayuki-san who was sent to Malaysia, and had not returned to Japan.

Coup d'État (1973) Kaigenrei by director Yoshishige Yoshida

Kaigenrei, which translates as 'martial law', documents an attempt to overthrow the Japanese government by the military in 1936. Yoshida's documentary shows how ultranationalist Ikki Kita's ideas inspired the unsuccessful coup.

Himiko (1974) by director Masahiro Shinoda

Himiko (Credit: Art Theatre Guild)

This freestyle fantasy shows the life of the shaman queen Himiko, who becomes significantly weakened when she falls for her half-brother. Now far less powerful than before, her position as queen is at risk.

Matsu the Untamed Comes Home (1974) Muhomatsu no issho by director Shōhei Imamura

A poor rickshaw driver, who is known for his good will, is hired by a couple after he helps their injured son. He soon becomes a valued member of their family, continuing to help them in times of need. Despite now being a part of the family, the driver is aware of a vast difference in social status dividing them.

Pastoral Hide and Seek (1974) Den-en ni shisu by director Shuji Terayama

Based on the director's own adolescence, Pastoral Hide and Seek is a coming of age tale that takes place in a small Japanese village.

God Speed You! Black Emperor (1976) Goddo supiido yuu! Burakku empara by director Mitsuo Yanagimachi

Centering on a member of the teen biker gang known as the Black Emperors, God Speed You! Black Emperor documents the country's sudden rise bōsōzoku (adolescent motorcycle gangs) and their clashes with the law.

In the Realm of the Senses (1976) Ai no korîd by director Nagisa Ôshima

Loosely based on real events, the film centers on a woman whose sexually experimental affair with her master leads to obsession, violence and tragedy. Oshima intended to show unsimulated sex in the film, meaning that the it had to be shipped to France to be processed. In a Japanese court, the director defended his decision, and even went on to make a companion film, Empire of Passion, in 1978.

For twenty years, the Japanese New Wave had provided audiences with politicized, experimental cinema that would ironically never have become so widely seen without its corporate beginnings. The movement created an overall acceptance for experimental techniques within Japanese cinema, and helped shape the country's media as we know it today. By 1976, the studio executives that had systematically decided Japan should create a New Wave for commercial reasons had become ostrasized by the movement, which was now largely lead by independent productions and free-thinking directors. In fact, the very same executives had become frustrated by their own creation, as their productions were now always expected to feature unadulterated content and strong politicized messages.

In the 1980s, Nagisa Oshima became significantly more recognizable in the West thanks to his acclaimed war drama starring David Bowie and Takeshi Kitano, Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence. Prior to this, after a decade-long devotion to documentary filmmaking, Shohei imamura returned to fictional narratives with 1979's Vengeance Is Mine. Teshigahara would also focus on documentary filmmaking, as well as his duties at the Sogetsu School, where he became the school's grand master in 1980. In the same year, counterculture icon Seijun Suzuki released the first installment of his Taishō trilogy; He would even go on to make a sequel to Branded to Kill in 2001, Pistol Opera, and collaborate with Zhang Ziyi for 2005's Princess Raccoon.

References

Turim, Maureen The Films of Oshima Nagisa: Images of a Japanese Iconoclast, pp. 51-60. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

Oshima, Nagisa. "In Protest against the Massacre of Night and Fog in Japan." Cinema, Censorship, and the State: The Writings of Nagisa Oshima, 1956-1978, pp 54-58. The MIT Press, 1992. Cambridge.

"Velvet Hustlers & Weird Lovemakers: Japanese Sixties Action Films". American Cinematheque. April 2007.

Palevsky, Nick (January 2009). "Koreyoshi Kurahara, Part II: 'The Warped Ones' and Its Antecedents". The Auteurs.

Desser, David (1988). Eros Plus Massacre. Indiana University Press. p. 62

Gragert, Bruce (1997). "Yakuza: The Warlords of Japanese International Crime". Annual Survey of International and Comparative Law. 4 (9): 157–159.

Kim, Nelson (July 2013). "Shohei Imamura". Senses of Cinema. Senses of Cinema (27): 3–10.

Berra, John (July 5, 2011). "Pigs and Battleships". www.electricsheepmagazine.co.uk. Electric Sheep.

James Quandt, Video Essay included on the Criterion Collection DVD release of Pitfall

Bradshaw, Peter (15 October 2010). "Sex, death and long grass in Kaneto Shindo's Onibaba". The Guardian.

Shindo, Kaneto (Director) (2008-05-15). Onibaba, DVD Extra: Interview with the director (DVD). Criterion Collection.

"Masahiro Shinoda in the 1960s". Melbourne Cinémathèque.

Suzuki, Seijun; Takeo Kimura (2005). Gate of Flesh (Interviews) (DVD).

Rayns, Tony (January 2005). "Fighting Elegy". The Criterion Collection.

Desjardins, Chris (2005). Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film. I.B. Tauris.

Vryzidis, Nikolaos (2010). "Tokyo Drifter Critique". Directory of World Cinema: Japan. Fishponds: Intellect Publishing.

James Quandt, Video Essay included on the Criterion Collection DVD release of The Face of Another.

Sato, Tadao (1982). "Developments in the 1960s". Currents in Japanese Cinema. Translated by Gregory Barrett. Kodansha International. p. 221.

Turim, Maureen Cheryn (1998). The Films of Oshima Nagisa: Images of a Japanese Iconoclast. Berkeley: University of California.

Oshima, Nagisa. "Notes on Boy," 1969. P. 170-182 in Cinema, Censorship, and the State: The Writings of Nagisa Oshima, 1956-1978, ed. Annette Michelson. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1992.

Buruma, Ian. “Behind the Mask: on sexual demons, sacred mothers, transvestites, gangsters and other Japanese national heroes,“ 1983. P.35 Penguin Books Ltd.