Even the most passive moviegoer will be familiar with the concept of montage. Their exhaustive use in 1980s Hollywood action films has led to countless parodies and a far more selective use of the technique from filmmakers ever since. However, there’s much more to montage theory than Rocky Balboa would have you believe, and it all started during the Soviet Union's early years.

How Soviet Montage began: The Kuleshov effect

OCTOBER: TEN DAYS THAT SHOOK THE WORLD (CREDIT: SOVKINO)

Just like French Impressionist cinema, Soviet Montage came from the concept that film theory doesn't necessary have to align with theatrical frameworks, as the filmmaking process provides an entirely new set of tools. Director Lev Kulshov first conceptualised montage theory on the basis that one frame may not be enough to convey an idea or an emotion. This would become known as the Kuleshov Effect. The audience are able to view two separate images and subconsciously give them a collective context. To prove his point, the filmmaker cut together various images, each of which changed the audience's reading: The same facial expression, applied to different situations, will be interpreted entirely differently by the audience depending on its collective context. In this way, Kulshov was applying tools more commonly associated with literature and language, forming sequences as you would a sentence rather than composing a scene as if it were a live theatrical production.

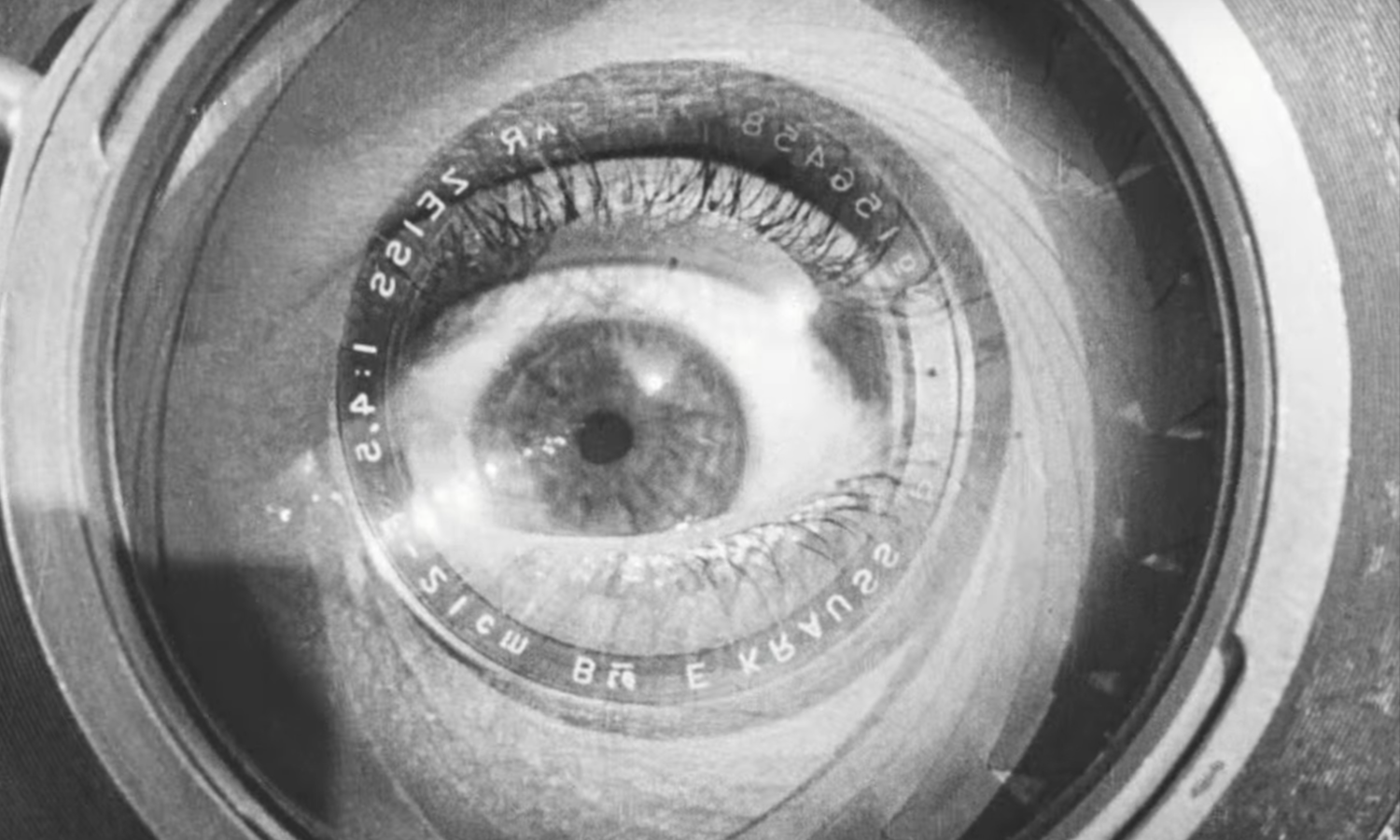

Kulshov’s theory asked questions as to how editing and composition influences a viewer’s interpretation of a sequence. He inspired filmmakers such as Sergei Eisenstein (Battleship Potemkin), who was formerly a student of Kulshov, and Dsiga Werov (The Man With a Movie Camera). Collectively, the directors utilizing montage theory were able to explore how time and space can be presented on film, exploring how audiences may respond to various montage techniques.

Although montage is generally used in less radical ways in modern cinema, Kulshov’s theory has undeniably become a common tool for filmmakers worldwide, and films such as Battleship Potemkin and The Man With a Movie Camera are still celebrated as some of the most groundbreaking films of all time. (Source)